Today only the watery foundations of the Elizabethan Rose theatre’s 14-sided timber structure are still standing on London’s Bankside (south of the Thames River), located about 100 meters from the new Globe theatre. The Rose Playhouse, built in 1587, housed the acting troupe known as the Admiral’s Men and their legendary Christopher Marlowe interpreter, Edward Alleyn. Recently the producers of Shakespeare’s Rose Theatre decided to allow playgoers to experience the intimacy of a Shakespeare play within the Rose playhouse. So they created a four-play repertory that could be performed inside two temporary structures that bear a striking resemblance to the Rose’s thatched roof and timber structure. These two Rose theatre facsimiles are notable for being open to the sun and… Read More…

SHAKESPEARE UNRAVELED

The Rose Theatre at Blenheim Palace Closes Richard III Under a Chilly Drizzle

Bate Explores Shakespeare’s Uniquely Elizabethan Debt to the Ancients

Elizabethan audiences had no expectations that the plots invented for the rowdy stages of London playhouses would be completely new and original. When Shakespeare developed the scripts of Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and other Roman plays, he adapted his plots from Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. In relying on a historian’s translation of these biographies (which Plutarch wrote for readers in the 1st-century A.D.), Shakespeare followed the literary fashion of his time. In How the Classics Made Shakespeare, the eminent scholar and critic Jonathan Bate nimbly revisits how the world’s greatest playwright relied upon sources like Plutarch and Ovid, but he offers a deeper, erudite investigation into how the sonnets, narrative poems, and plays are inspired by other canonical “ancients” such as Cicero, Horace, Seneca, and Virgil. This latest book cogently builds upon Bate’s ambitious work, Soul of the Age, a biography of Shakespeare’s mind, and his earlier Shakespeare and Ovid.

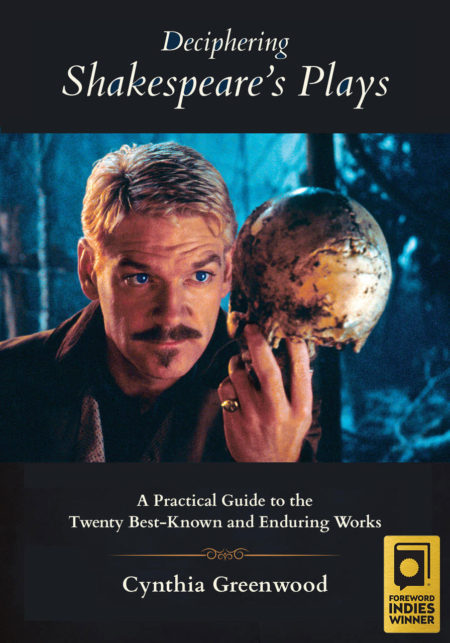

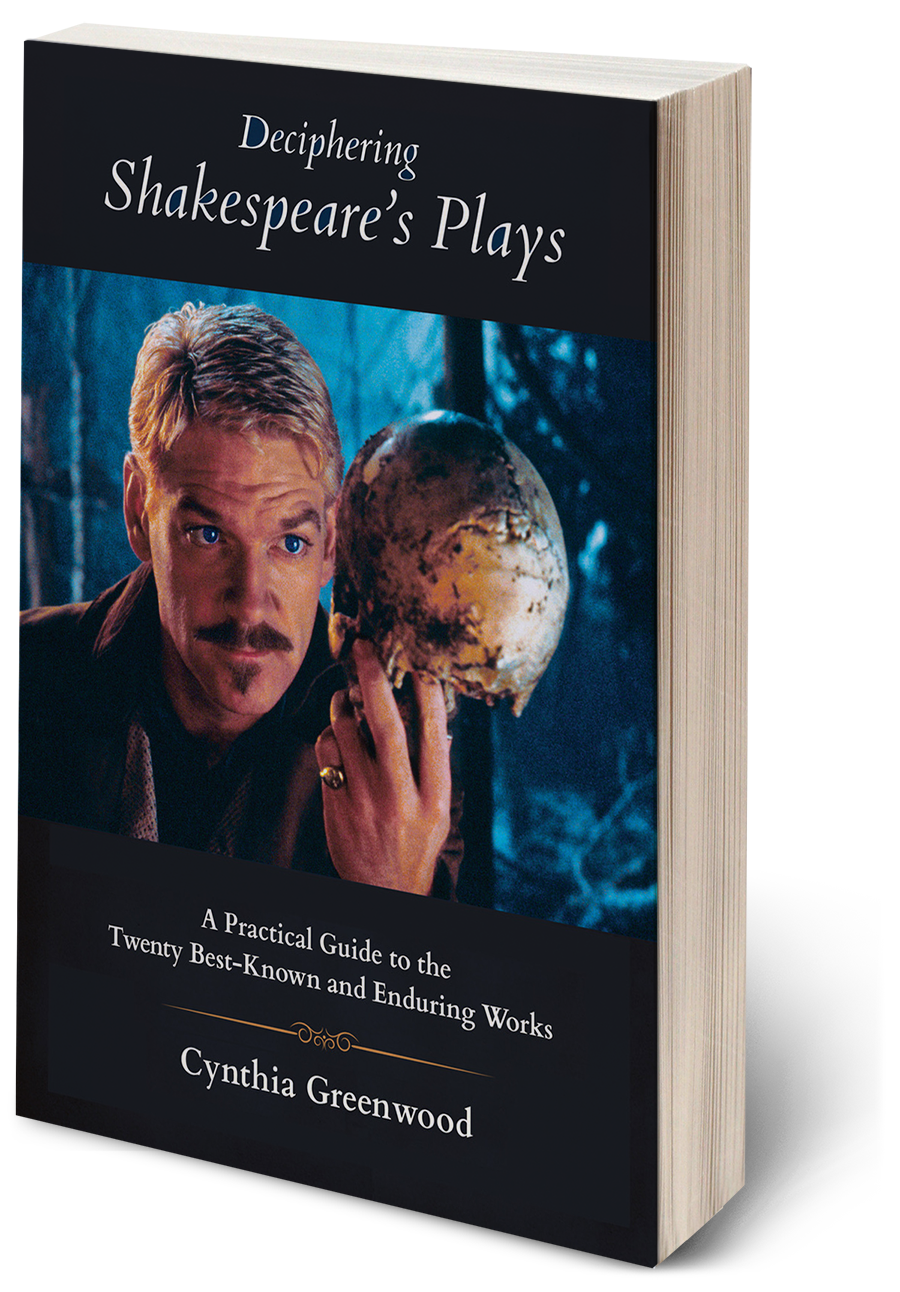

Deciphering Shakespeare’s Plays receives the Foreword INDIES top prize for Reference nonfiction in annual Book of the Year Awards

TRAVERSE CITY, Michigan: June 14, 2019—Foreword Reviews, a book review journal focusing on independently published books, announced the winners of its INDIES Book of the Year Awards today. The awards recognize the best books published in 2018 from small, indie, and university presses, as well by self-published authors. You can view all of the winners here: https://www.forewordreviews.com/awards/winners/2018/ “Being surrounded by the year’s best books from independent writers and publishers is a humbling and invigorating experience that we take seriously at every step of the judging process,” says Managing Editor Michelle Anne Schingler. “As the INDIES progress, our editors, and our librarian and bookseller judges, have the honor and the privilege of discovering and rediscovering independent titles that give us hope… Read More…

New Illustrated Edition Reimagines Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” in Verse

Anyone familiar with Charles and Mary Lamb’s 1807 classic, Tales From Shakespeare, will appreciate the motive behind Peter and William Blagys’s new 11- by 17-inch illustrated edition, The Rarer Action: Shakespeare’s The Tempest Retold. As those who tend to be skittish about reading Shakespeare’s plays will discover, this wry, charming retelling of the bard’s most popular romance is much more zany and whimsical than Mary Lamb’s earnest prose adaptation of The Tempest (also adorned by vivid color plates). Both works, however, share an important and practical aim—to recount the adventures of an exiled duke and his young daughter in an entertaining and accessible manner. The Rarer Action is a collaboration between two brothers—writer Peter W. Blagys and illustrator William A. Blagys—and it is a novel retelling of The Tempest with… Read More…

Riedel’s Merchant is Scintillating, Despite Our Aversion to Shylock’s Undoing

The Merchant of Venice is part of Shakespeare’s “controversial canon” of plays for today’s theatre-goer. Directors persistently wrestle with audience concerns about the playwright’s bias against the drama’s notorious money lender who is robbed of his religion during the final act. Because Shakespeare most likely styled his play after Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (1589), he conceived of Shylock as an allegorical figure from medieval drama—a stereotypical bad guy that Elizabethan audiences had grown to expect in the 1590s, when Merchant was first performed. A lesser playwright would have imagined Shylock as a one-dimensional villain. Shakespeare, though, created a well-rounded anti-hero who roundly exposes Christian hypocrisy, and challenges the ignorant prejudices about Jews that were displayed by his countrymen…. Read More…