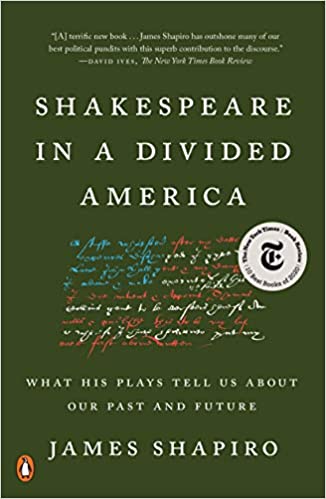

In his latest book, Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Future, the esteemed Shakespearean James Shapiro (author of The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606) shifts his focus to America’s fascination with Shakespeare over the past two centuries. This new work of history comes six years after the author edited a notable compendium of short pieces by renowned American poets, presidents, novelists, statesmen, humorists, artists, and critics, titled Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now.

Acknowledging the impossibility of tackling a complete history of Shakespeare in America, Shapiro aims to “drill down more deeply into eight defining moments in America’s history.” By isolating specific historical episodes dating back to 1833, he reveals through meticulous research how the invocation and appropriation of Shakespeare exposes lesser-known patterns of racial, class, and gender inequality that persist amid today’s culture wars.

Shapiro starts by probing the letters and published articles written by former president John Quincy Adams, which “vilified Desdemona for desiring and then marrying a black man.” The existence of such tendentious writings should puzzle us today in light of Adams’s renunciation of slavery as early as 1783, and his record as an abolitionist while in Congress between 1831 and his death in 1848. In a chapter that brings early nineteenth-century attitudes about miscegenation into full view, Shapiro offers a fascinating analysis of Adams’s very public denigration of Desdemona’s interracial marriage.

Shifting to the run-up to the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, Shapiro lends insight into a forgotten period of Anglo-American theatrical history — a time when a young thespian and future president named Ulysses S. Grant rehearsed the role of Desdemona for an Army theatre production of Othello, a part he never performed. We learn how views of manly superiority and Manifest Destiny held sway as thousands of bored, idle Army troops encamped in Corpus Christi in the summer of 1845. Ironically, around this time the contralto-voiced, cross-dressing actor Charlotte Cushman interpreted Romeo to great critical and popular acclaim in New York and London. Shapiro discusses why “the polite, courtly (and often aging) Romeos that reigned on both sides of the Atlantic were duds.”

Shapiro offers an impressive study of the origins of Abraham Lincoln’s deep reverence for Shakespeare, juxtaposed against the Shakespearean obsessions and racist radicalization of John Wilkes Booth. Shapiro states, “Abraham Lincoln had seen Booth act and knew Shakespeare’s plays as intimately as his murderer did.” Shapiro also explores Lincoln’s particular identification with the speeches of evil characters in Richard III, Macbeth, and Hamlet. In a book that enlightens as well as disturbs, the portraits of these two Shakespeare aficionados are replete with irony.

Although the popularity of The Tempest waned in the middle decades of the twentieth century, Shapiro enlightens us about a time in 1916 when the play was at the forefront of American consciousness. That year, more than three hundred thousand spectators in New York and Boston saw a staging of Caliban by the Yellow Sands, Percy MacKaye’s adaptation of The Tempest. According to Shapiro, “Through its portrayal of Caliban, and in its reliance on large groups of performers from different ethnicities, the production spoke to one of the most divisive issues of the day — immigration — a concern that was being fiercely debated in Congress, [with] discussions that would lead to the passage of ground-breaking legislation …. redefining who could be an American.”

This compelling moment coincided with a period from the 1880s when America’s tolerance of northern European immigrants transformed into palpable anxiety around 1898, as greater numbers of southern Italians and Eastern European Jews sought refuge here. Shapiro traces the growing exclusionary nature of U.S. immigration policy and the ways in which The Tempest was adapted and appropriated to justify racism against generations of immigrants.

The book offers an intriguing, deeply researched inquiry into the controversy over marriage that characterized the development of Kiss Me, Kate, the 1948 musical adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew. Equally entertaining is Shapiro’s anecdotally rich account of how the film, Shakespeare in Love, evolved over a decade. I’ve always admired how well Shakespeare in Love appeals to viewers who may know a little or a lot about Shakespeare. The film’s use of historical detail is subtle and sophisticated. But I’ve always been curious about the dual screenplay credit. As it turns out, the original script that was pitched by Hollywood screenwriter Marc Norman to producer Edward Zwick in 1991 bore little resemblance to the final revision penned by eminent British playwright and screenwriter Tom Stoppard.

Norman’s script incorporated racy themes of adultery and homoeroticism, shattering norms of heterosexuality. Over time, Stoppard was brought in, and recommended improvements to the Elizabethan historical context. In the process, Norman’s themes and structure were scrapped in favor of a sharper plot and dialogue, and a more accurate narrative. Shapiro’s account of the evolution of the script and numerous changes to the film’s ending is highly entertaining.

“Those who have seen the 1998 film will likely be surprised by how much more progressive Norman’s 1991 version of the love story had been,” Shapiro notes. Ironically, both writers earned an Oscar for Best Screenplay for hugely disparate visions of what the film should be.

Shapiro concludes with an in-depth account of the controversial 2017 production of Julius Caesar at the Delacorte Theatre in New York’s Central Park. By situating the Roman play in a context in which Donald Trump resembled Caesar, the show caused a firestorm in the right-wing media. (Eustis conceived of the show as a follow-on to Stephen Greenblatt’s New York Times op-ed that compared Trump to a Shakespearean tyrant.) Shapiro illustrates how misperceptions about Eustis’s adaptation and a general ignorance about the play itself stoked enough controversy to alienate the show’s sponsors and endanger the lives of the actors onstage.

Shakespeare in a Divided America offers a cogent study of how the world’s greatest playwright has been invoked, appropriated, and implicated — to American society’s great detriment. Once again, an author who many of us know from books that are steeped in Elizabethan and Jacobean theatrical history, has demonstrated his intellectual reach as a historian of the highest caliber. Documentary photographs, paintings, drawings, and theatrical posters illustrate each historical episode. Shapiro also provides his usual detailed, engaging bibliographical essay for each chapter.

This review was originally published at PlayShakespeare.com.

Consider me a professional interpreter of William Shakespeare for intelligent readers who never warmed up to the world’s greatest playwright in high school or college. I delight in helping modern readers and audiences translate iconic texts, especially antiquated dramatic works that were meant to be experienced inside the theatre.