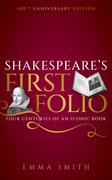

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio, Oxford professor and scholar Emma Smith has revised and re-issued her 2016 study published by Oxford University Press, Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book. Unlike historians who have examined how Hemings and Condell (two of Shakespeare’s fellow King’s Men actors) came to produce a collection of Shakespeare’s plays alongside publishers Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, Smith delves into the reading and collecting habits of those who have bought and sold the First Folio since it debuted in 1623.

Smith’s study “begins in the retail bookshop” where early buyers such as Edward Dering may have acquired his first copy. She exhaustively explores how the First Folio “has moved through [four centuries of] time, space, and context.” To do so, she pores over numerous editions of the book, whose early owners can be traced through doodling, markings, comments, and habits of close reading and engagement with the plays.

Using the art historian’s practice of tracing the provenance of an individual painting, she superbly reconstructs the provenance of several of the best-known First Folio editions. (There are 235 First Folio volumes known to us today.)

Relying on a close reading of myriad First Folio copies in private and institutional hands, Smith divides her study into five main parts. She looks at the motives of various individuals for owning a First Folio; the distinct “habits of reading” by owners, and what their page markings actually tell us; how early influential editors have “decoded” the First Folio in their desire to recapture Shakespeare’s lost original manuscript; how theatre professionals have used the First Folio for acting in and staging plays; and the methods and motives of owners who sought to restore or improve the binding and interior condition of their volumes.

In her initial chapter titled, “Owning,” Smith impressively constructs a detailed provenance of notable First Folios, complete with colorful details about their respective owners. Whereas any First Folio is regarded today as an extremely valuable artifact that would be expensive to acquire, to the early modern user, the book itself was not coveted at all by booksellers or antiquarians.

Things began to change, of course, as Shakespeare’s reputation grew. By the nineteenth century, J.P. Morgan would have counted his First Folios among such prized collectibles as his notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci and keepsakes belonging to Catherine the Great, Napoleon, and George Washington. It makes sense, of course, that “the value that has accrued to the book is a reflection of the value of Shakespeare himself,” Smith argues.

Today, more than one third of extant First Folios are owned by the Folger Shakespeare Library, thanks to the “collecting energy of Henry Clay Folger at the turn of the twentieth century,” Smith tells us.

In her first case study, Smith traces the provenance of a First Folio initially acquired by 1650 by William Sheldon, or possibly his son Ralph, who were from Warwickshire. Ralph Sheldon’s Restoration-era library included this particular edition when it was sold off in 1781. The “Sheldon”edition moved into the collection of “radical politician,” John Horne Tooke, who believed that First Folios, in general, were unique among the four folio editions published between 1623 and 1685. Tooke gave his copy to Sir Francis Burdett, a politically like-minded MP. Burdett’s philanthropist daughter, Angela Burdett Coutts, inherited her father’s First Folio. After Burdett Coutts acquired a second First Folio owned by George Daniel for the much-publicized price of 714 pounds, she became one of the most famous First Folio collectors of the nineteenth century. Both the Sheldon and Daniel editions owned by Burdett Coutts were sold in 1864 to A.S.W. Rosenbach, a bookseller and collector who acquired them on behalf of Henry Clay Folger. Today they sit among the 82 First Folios housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

Besides tracing the provenance of the Sheldon First Folio, Smith explores the colorful provenance of the Bodleian First Folio. Such case studies demonstrate how folio editions came to leave England for other parts of the world, and how they shifted back and forth between private and institutional owners.

Smith’s scrutiny of myriad collections reveals how the First Folio evolved from being an object of study and reverence by Restoration-era and eighteenth-century theatre producers into a pricey artifact. Morgan, Folger, and other wealthy collectors were instrumental in transforming the First Folio into a commodity, i.e., a thing to be traded and “monetized”.

In her chapter titled, “Reading,” Smith has answers for anyone wondering whether First Folio owners actually read the book in their possession. For a century or so after its release in 1623, “the Folio was often intensively read and used, as extant copies can attest,” she explains. Indeed, early modern owners engaged with the plays extensively, and she analyzes the grease marks, doodles, stains, and scribbles made by specific owners who marked up their folios during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Textual scholars and cultural biographers should appreciate Smith’s chapters on owning and reading the First Folio, which comprise more than half the book’s 343 pages. But scholars committed to teaching Shakespeare to students and playgoers may find these sections less engaging than the chapters dedicated to “decoding” and “performing” the First Folio.

Educators who rely on modern editions of Shakespeare’s complete works will appreciate Smith’s investigation of eighteenth-century play editions compiled by Nicholas Rowe, Alexander Pope, Lewis Theobald, Samuel Johnson, and others. All were trying to modernize Shakespeare, and they challenged the primacy of the First Folio text through their script emendations. With the release of his six-volume edition in 1709, Rowe, a lawyer and playwright, “established the informed editor as the key authority in the accurate transmission of Shakespeare’s text, and his own work set out the model for the work of that intermediary,” Smith argues.

Smith also explores the groundbreaking editorial work of Edward Capell and Edmund Malone, who “established the importance of the First Folio text in the transmission of Shakespeare’s plays. Capell’s multi-volume Shakespeare edition of 1767-68 offered “a new collation of the texts” and established the primacy of the First Folio “for all the previously unpublished plays and for a number of quarto texts,” she concludes. The rigor of Capell’s method greatly influenced Malone, the eighteenth-century editor whose multi-volume play edition of 1790 established a new and lasting paradigm for modern editors.

Until sixty years ago, prior centuries of editorial work on Shakespeare’s plays was driven by a desire to emulate his “lost manuscript, or his lost intentions or his lost originals,” Smith points out. But in 1963, Shakespeare textual studies underwent a sea change when the Shakespeare scholar Charlton Hinman applied his expertise as a naval cryptanalyst (codebreaker) during the Second World War to understand textual variations within the entire First Folio collection at the Folger Library.

Hinman’s invention of a collator machine revolutionized the course of Shakespeare textual studies. In his 1963 work, The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio of Shakespeare, Hinman showed us how variations in spelling, capitalization, spacing, and individual letter pressing within the plays of the 1623 folio could be attributed to a group of anonymous printshop employees, whom Hinman identified as Compositors A, B, C, D, and E. As Smith points out, “Hinman’s work set the agenda for mid-twentieth-century bibliography,” and many editors made use of his patented collating machine for textual studies of other canonical works.

As a theatre historian who impresses upon students and playgoers the importance of appreciating Shakespeare’s plays in performance, I was especially drawn to Smith’s intricate look at methods of the first serious editors of Shakespeare’s plays. Experts in early modern drama should also appreciate her chapter on decoding, and how scholars today are indebted to the work of Capell, Malone, Hinman, and many others.

The author’s analysis of how famous Restoration, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century playwrights, directors, and actors used and interacted with the First Folio in her chapter titled, “Performing,” should also fascinate theatre historians, scholars, and teachers.

Note: This review was originally published at PlayShakespeare.com on January 23, 2024. Visit https://www.playshakespeare.com/the-complete-works-of-shakespeare/book-reviews/15750-the-first-folios-evolution-from-an-iconic-book-into-a-priceless-artifact

Consider me a professional interpreter of William Shakespeare for intelligent readers who never warmed up to the world’s greatest playwright in high school or college. I delight in helping modern readers and audiences translate iconic texts, especially antiquated dramatic works that were meant to be experienced inside the theatre.